Director’s Note

Bryson Tiller once said, “So gimme all of you in exchange for me.” I couldn’t find a better way to describe the process of this play. It was truly an exchange in which everyone gave the best of themselves to create one story that spoke to many generations, many experiences, and many people.

The journey of this play began in April when 19 students logged into Microsoft Teams with me to decide how we would write a story that spoke to their experiences of the campus. We didn’t know exactly what that would look like but we knew it would be at times scary, at times romantic, and always real. As the story unfolded, we learned about the importance of collaboration. When one student would share a vulnerable truth, another student would be inspired to dig deeper into their own unexplored realities. And thus the process of exchanging cultivated what you will see in the play…or rather, multi-media digital storytelling experience.

Even the learning process was an act of exchange. I was technically categorized as a teacher, but I was also a student to the knowledge the writers so generously gave. I taught them about the techniques of playwriting and they taught me about the campus culture of Kalamazoo College, their personal journeys with identity, and even their desire to see people of color have happy endings instead of trauma narratives. We exchanged my love of structure and their love of honesty and found a powerful story that validated students and educated others.

Now it’s time for you to exchange with us. As an audience member, you embark on the journey, not only by watching, but by sharing, commenting, and connecting with us digitally to expand our connection and help this story live on and evolve.

I hope you reflect on this story and are inspired to share your own truths via…whatever format resonates with you.

—Emilio Rodriguez, Director

Dramaturgical Essay

At ACTF in 2018, Laura Livingstone-McNelis and Lanny Potts sat down to meet with two theatre makers to talk about their work. That discussion with Emilio Rodriguez and Jens Rasmussen planted the seed of our department’s devised theatre project. Over the following year, plans were made with both of these artists, and we added a performance of the project to our 2020-2021 season. But, before this performance could happen, we needed to not only help the students devise and write the piece, but learn how devised performance works.

The first step in the process came in March 2020, at the end of our Winter Term, with a visit from Jens Rasmussen who ran a series of workshops based on the work he has done with the Bechdel Project in New York. He split the workshop into one track focusing on movement and the other focusing on the written word, with participants allowed to participate in both tracks. On the final day, our students came together to bring movement to the words they had worked on, combining the tracks.

The actual devising for our season was set to commence in Spring Term of 2020. Emilio Rodriguez, a Detroit based artist and artistic director of Black and Brown Theatre Company, was scheduled to come lead the efforts as a guest artist and lecturer on campus. However, as we all know, the lockdown for COVID-19 began at that point. However, that did not stop us from moving forward with our project. So, while we were not blessed with Emilio’s presence physically on campus, the process continued virtually online.

Each week, Emilio would meet with two different groups to push this project forward. The first group was the Community Dialogues class, where the students served as the playwrights for our production. As a class, they would do various writing exercises to encourage them to explore character and plot, while also talking about the issues on campus that were most important to them. The writing that came out of this class each week could potentially become part of the play, but always helped the students identify how to explore issues important to them through theatre.

This writing would then be taken to a volunteer group of students who spent their Saturday mornings doing improv exercises and reading the results of the Community Dialogues class. Their feedback could then be received by the class each week, shifting the directions they were taking and helping them understand when their message was being received so they could be more effective writers. At the end of ten weeks of class, there was a working script of K that could be refined over the summer and brought to a cast for performance this fall.

At the core of this script, the issue the students most wanted to deal with was the experience of students of color at Kalamazoo College. Like most PWIs (Predominantly White Institutions), Kalamazoo College has both explicitly and implicitly participated in the marginalization of students of color over the course of its history. Explicit examples include the performance of blackface in an annual minstrel show up through the middle of the 20th century and the conflict between Weimer Hicks and the Black Student Organization in the 1960s.

Carrying on for years up through the 1950s, minstrel shows like the “Darktown Jamboree” were performed on Kalamazoo College campus. A minstrel show is a collection of songs, skits, dances, and comedy routines (similar to a vaudeville act), where Black characters are played by white actors in blackface. Under pressure from the Kalamazoo community, and from faculty like Nelda Balch, Weimer Hicks worked with the performers to make the shows less offensive before ultimately abandoning the tradition.

In the 1960s, a number of Black power speakers visited Kalamazoo College, and due to their influence, the Black students on campus formed the Black Student Organization. This organization immediately encountered resistance from the student commission and Weimer Hicks. Their fight for their rights is detailed in a series of letters between the organization and Hicks as well as in memos from Hicks to other members of the administration at the time and can be found in the College’s archives.

The implicit marginalization can be harder to see. Despite successful efforts to increase student diversity – demographically our student population is more diverse than the population of Michigan – students can often feel that they do not have mentors to look to as our faculty demographics are not as diverse as that of our students. Also, even with staunch supporters like Nelda Balch, who pushed to stop the performance of blackface on campus, students of color still did not feel fully represented, with the mainstage dominated by white actors and roles for students of color more often being available as part of independent projects, either the Senior Performance Series, or through organizations created to serve students of color.

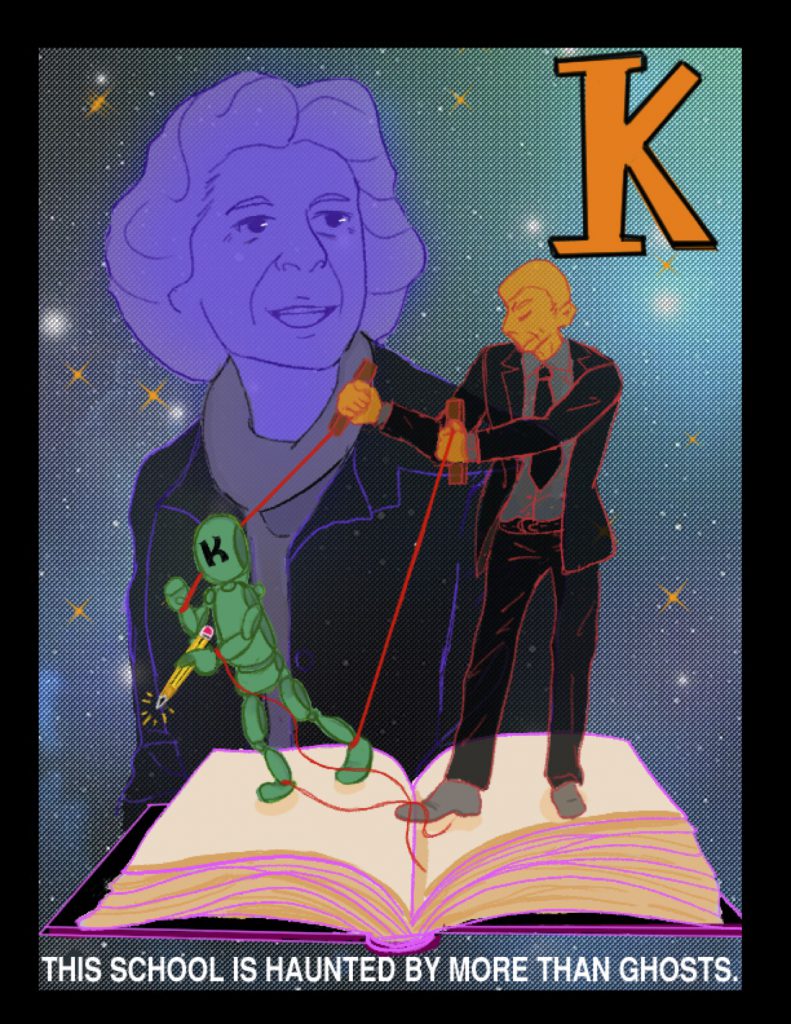

It should not be a surprise that our students focused in on this issue as they were writing at the beginning of renewed activism in the face of George Floyd’s death. Many of the students in the class were people of color and had much to share about their own struggles with identity and belonging. The history of racism inherent in any institution of power in America is what haunts our campus in addition to the ghosts of Balch and Hicks in this play by our students.

After finishing the play, when deciding on a title the students settled on the title K, for its dual meaning. It represents both the specifics of our K campus community addressed within the play, but also the multiplicity of meaning available in the short statement of “k”, as in short for “okay”. It can be a resigned acceptance of what is presented but it can also represent the moment’s pause before launching into a new plan of action. And our students have that plan.

—Dr. “C” Heaps, Dramaturg

SOURCES:

Various letters and books from the Kalamazoo College Archives

Johnson, Janay. “From Blackface to Black Power: K’s Changing Racial Climate in 1950s and 1960s.” The Index. 19 April 2017.